Building a Game With TypeScript. Ship and Locomotion

Chapter IV in the series of tutorials on how to build a game from scratch with TypeScript and native browser APIs

Welcome to the final installment of Chapter IV! Last time we hit the wall with the position of the Ship. We prepared ShipDrawComponent following Test Driven Development mantra and even saw it in action on the screen. However, we hardcoded the position property. We realized that this attribute of the Ship depends on something totally foreign for us yet: the notion of moving the Ship. This time we are going to make things right.

In Chapter IV “Ships”, we are implementing the most important token of our turn-based game: we are drawing the Ships. Players will use them to attack other players. Losing all ships means losing the game. You can find other Chapters of this series here:

- Introduction

- Chapter I. Entity Component System

- Chapter II. Game loop (Part 1, Part 2)

- Chapter III. Drawing Grid (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5)

- Chapter IV. Ships (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

- Chapter V. Input system (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

- Chapter VI. Pathfinding and Movement (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7)

- Chapter VII. State Machina

- Chapter VIII. Attack System: Health and Damage

- Chapter IX. Winning and Losing the Game

- Chapter X. Enemy AI

Feel free to switch to the

ships-3branch of the repository. It contains the working result of the previous posts and is a great starting point for this one.

Table of Contents

- Introducing Locomotion Component

- Accessing Position

- Spawning Ships

- Wrapping up

- Conclusion

Moving a Ship is not the responsibility of the DrawComponent. Behaviors “move” and “draw” should be completely independent of each other. We could argue that Ship as an Entity may possess such functionality. Yet, why would it be? We may have an unmovable Ship. Even more, we can deny Ship its right to move at different stages of the game, making it a runtime behavior, not a core attribute of a Ship. It means, “movement” is a component. So, let’s create one!

Introducing Locomotion Component

Why “locomotion”? We were talking about the Ship’s movement, why not call it “ShipMoveComponent”? In turn-based games term “move” usually refers to something players do to achieve their goals. “Make a move” in our game will mean not just the Ship relocation but also attack, increasing defense, etc. We will talk a lot about it when we start implementing state machines and enemy AI. At that point having the same term “move” for two different concepts may cause a lot of confusion. To avoid it, allow me from now one name ship’s movement “locomotion” or “relocation”.

We start by defining boilerplate for the new component:

And creating/updating respective barrel files:

Now, let’s take a second to think briefly about the movement itself. We won’t dive too deeply (that’s a topic of discussion for the next chapters) but we have to grasp the basic idea. First, the Ship does not change its position arbitrary. It can only move between nodes:

When the Player selects Node, active Ship finds its path to that Node. If we ignore animation and pretend Ship changes its position instantly, we can see that at any given point Ship can be located only at that center of some Node.

To accomplish this, we ask ShipLocomotionComponent to hold a reference to the Node this Ship currently stands on (assuming there is any):

It is possible for Ship to stand kind of “nowhere”. Or, to be more precise, not on any Node. Hence, _node can be null. Obviously, Ship can change its position, that’s the purpose of this component. We define public setter as a way for external code to signal that position should be changed. How exactly it will change is up to LocomotionComponent to decide.

Now, we can use this _node reference to determine the position of the Ship. But Node is an area, while the position is a specific point. Which point of the Node should we use? Let it be the center of the Node:

Here we calculate the center of the Node using its start point and size. However, it looks a bit bloated, and probably not the best place for this kind of logic in the first place. Let’s move it to the Node.

The Center of the Node

We can make exact same calculations within Node and provide a public getter for it:

Awesome! Also, while we are in the neighborhood, we should update the tests for Node. First, let’s update spec to use Node's mock:

Nice! Now we can add a new case:

We expect that this new Center property of ours returns indeed a center point of the Node:

With that in place we can simplify the Position getter of the LocomotionComponent:

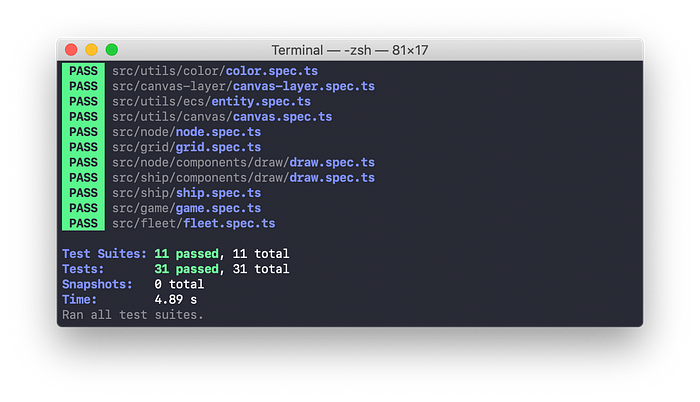

Awesome! At this point, our code should successfully compile with npm start and all test should pass with npm t:

Accessing Position

Now we can attach this newly created component to the Ship entity:

Yet, how can DrawComponent access Position property? It has no direct access to it, and it should not. But it has access to the entity, which in turn can access all its components.

I start by defining hardcoded Position property within Ship instead of DrawComponent:

Now DrawComponent can rely on it:

Note, ShipDrawComponent requires a Position to exist. If it doesn’t, the component throws an error. Which, from an application design perspective, means before we start using this component, we must ensure it stands “somewhere”.

For Ship to get a position from Locomotion it has to have access to reference to it. Of course, it could use GetComponent, but we better cache the reference instead:

A few things happen here. First, we define a read-only field to hold an internal reference to LocomotionComponent. Then we create and assign it within the constructor. Since it’s read-only, a constructor is the only place we can do it. Finally, we attach the components when Ship awakes. Note, we don’t have to instantiate and attach a component at the same time.

Having this, accessing Position becomes a trivial matter of accessing the public property of the reference:

Spawning Ships

Well, that compiles. But attempt to run our game in the browser would fail miserably. ShipDrawComponent screams at us, claiming that we forgot to set up Node for the Ship. Thanks, ShipDrawComponent!

Indeed, we are missing a key part of the puzzle. We have forgotten to specify where Ship actually is right now.

“Hold on a second! You told us it can stand nowhere!” Sure it can. But then we have to turn off ShipDrawComponent, what’s the point of drawing something that stands “nowhere”?

However, it is not the case now. Ships should spawn somewhere at the beginning of the game. The Player will relocate them with LocomotionComponent later, but at the very beginning, we have to set up initial position.

Moreover, we can agree that while Node is not a core feature of the Ship (it’s neither its property nor field) it still can be required to initialize it:

We can think about it as of “initial node” of a Ship, place it spawns on. We don’t preserve this information but pass it to the LocomotionComponent:

Of course, all references to the Ship constructor must be updated. We have only two so far: fleet.ts and ship.mock.ts (we were wise enough to define a centralized mock!)

The reason we have Fleet in the first place, is that we can make a centralized decision about all Ships of one player. For example, we can spawn player’s A ships on the left side of the board, and all ships of player B on the right. But to achieve that Fleet requires access to the Grid:

Here we make Grid a private required read-only field of the Fleet. Indeed, we are not going to re-assign it during the lifetime of the Fleet. In fact, for now, we only need it to access Nodes.

I will use this new field of Fleet to spawn Ships on different sides of the board, depending on what Team this Fleet belongs to:

Nice! Of course, we have to update Game now to fulfill the new signature of the Fleet:

TypeScript graciously reminds us that we also have two mocks to update:

And one for Ship:

Our code compiles again. Moreover, if you open it in the browser you can see this beautiful picture:

Nicely done! However, our tests are still falling.

Wrapping up

This happens because Fleet tries to instantiate and awake Ship, which requires a proper setup of Node and LocomotionComponent. The thing is, it is no concern about the fleet.spec.ts, it should verify only Fleet. So, we can simply mock Ship to remove this burden from its shoulders:

And since we are talking about tests, we should update ship.spec.ts to cover setup of LocomotionComponent:

We test the same way we tested ShipDrawComponent: by spying on awake and update methods and verifying they are executed only when respective methods of Ship being called.

At this point, our code should successfully compile with npm start and all test should pass with npm t:

You can find the complete source code of this post in the

ships-4branch of the repository.

Conclusion

Congrats, you made it! This was the last part of Chapter IV “Ships”. It was a long run, but we should be proud of ourselves! Just think about how much we have accomplished!

We started by introducing a new utility: Color that helps us deal with RGBA colors within the game. Then extended our humble rendering engine and made it render circles. And then we added a new canvas layer, “foreground”, preparing the stage for the key elements of the gameplay: Ships. We made sure this layer always stays on top of others so Ships won’t be accidentally blocked or painted over something else.

Also, we spend some time deliberating about conflict in games and the notion of “team”, which led us to introduce new members of our system. And then we jumped straight to the Fleet, a collection of Ships. We used it to awake, update, and spawn all Ships that belong to a particular Team.

Finally, we drew the Ships! We did so by introducing 2 new components: Draw and Locomotion, since Ship has to have position Node to be shown.

What is next for us? We are not yet done, we have so many features to introduce! In the next chapter we are going to look into interaction: how can Player command Ships to relocate them. We will start by implementing the Input system and thinking about the feedback game must provide to the player. I am looking forward to seeing you soon!

I would really love to hear your thoughts! If you have any comments, suggestions, questions, or any other feedback, don’t hesitate to send me a private message or leave a comment below! If you enjoy this series, please share it with others. It really helps me keep working on it. Thank you for reading, and I’ll see you next time!

This is Chapter IV in the series of tutorials “Building a game with TypeScript”. Other Chapters are available here:

- Introduction

- Chapter I. Entity Component System

- Chapter II. Game loop (Part 1, Part 2)

- Chapter III. Drawing Grid (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5)

- Chapter IV. Ships (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

- Chapter V. Input system (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3)

- Chapter VI. Pathfinding and Movement (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7)

- Chapter VII. State Machina

- Chapter VIII. Attack System: Health and Damage

- Chapter IX. Winning and Losing the Game

- Chapter X. Enemy AI